The other day while I was driving, the radio announced the death of Swedish poet Tomas Transtromer. I saw behind my eyes the green and white cover of his collected poems on my shelf at home.

The other day while I was driving, the radio announced the death of Swedish poet Tomas Transtromer. I saw behind my eyes the green and white cover of his collected poems on my shelf at home.

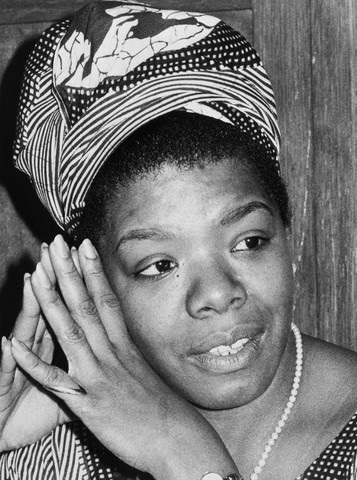

This same scene, but with a different book cover, occurred a few weeks earlier when I heard that Philip Levine had died. And in the months prior to that, the radio had announced the passing of many others: Stanislaw Baranczak, Claudia Emerson, Mark Strand, Galway Kinnell, Carolyn Kizer, Seamus Heaney, Maya Angelou.

And those are just the poets. Chinua Achebe, Nadine Gordimer, Doris Lessing, and Gabriel Garcia Marquez have left, too.

The rational part of me knows that artists whose work has mattered on a great and public scale are mortal. But the poets who have recently passed are those whose work I came of age with, and their collective departure seems a marquee announcing my entry into middle-age. It reminds me, too, that my friends are losing their parents, and our conversations and holiday cards always carry something of the quickening of mortality. In this, I have become more aware than ever of the fact of fiction: in death, everyone becomes a character steeped in legend, existing in a world apart from the one I watch and walk in.

The one comfort is that, when it comes to the loss of a writer, their books remain. Whether or not it is right, whether or not I know better, I often equate a writer’s books with their individual, real mind, and so a writer’s death does not feel so much a loss as it does a passage of the body. Even after their breath has ceased and their flesh has grayed, I can still enter a writer’s mind. In this way, the writer seems still of this world. The loss feels less sharply-edged.

The one comfort is that, when it comes to the loss of a writer, their books remain. Whether or not it is right, whether or not I know better, I often equate a writer’s books with their individual, real mind, and so a writer’s death does not feel so much a loss as it does a passage of the body. Even after their breath has ceased and their flesh has grayed, I can still enter a writer’s mind. In this way, the writer seems still of this world. The loss feels less sharply-edged.

But two deaths in the past year or so, both poets, caused me to weep. And when I take these writers’ books off my shelf, despite my best efforts, something tightens in the back of my throat.

On the surface, Wanda Coleman and Maxine Kumin might seem as different as a subway and a horse-cart: Coleman an urban, black, Los Angeles poet, and Kumin, a rural, white, New Englander. Likewise, Coleman and Kumin’s subject matter and style seem to come from opposite ends of the earth. Coleman’s work is a study in the brutality and compassion of a city, and the racism and poverty endemic to her geography. Her work is often described as playful, experimental, edgy – but those are code words for outspoken, sexual, outraged. Until I read Coleman, poetry was pretty. She made poetry real, the way a woman should be real: “we belonged to the same club, you and i … the unrepentant women with strong loves & stronger woes /the women accused of & found guilty of / taking their spare lives too seriously, the women / who rudely refused to bend for the soulfuck // the women who live on the astonished wind.”[i]

Kumin, on the other hand, is praised as a formalist, and her subjects include neighbors, family, her horses and garden, and the fraught yet natural cycle of life and death: “we can almost discuss it, good and harm. // Nature a catchment of sorrows. / We hug each other. No lesson drawn.”[ii]

Yet both women were fiercely political, intensely aware of injustice in the lives of others both like and unlike themselves. They lived and wrote on their own terms, aspiring to what they wanted from their art. They made no compromises, no excuses, no complaints.

However, despite a prolific number of books and critical acclaim, Coleman for many years struggled to make a living from her art. And Kumin, despite a Pulitzer Prize and teaching positions at prestigious institutions, remained in the shadow of her short-lived and more anthologized friends, Anne Sexton and Sylvia Plath. The steely resilience of Kumin and Coleman, in the face of the racism and sexism that permeated their personal and professional lives, remains for me one of the best lessons in what it means to live an honest and authentic life as a writer, yes, but also as a human being.

I met Wanda Coleman once, in the early 2000s. She came to Pittsburgh where I was a student, and in those years I didn’t know what to say to a writer whose work I admired (if I’m honest, ten years later, I have the same problem). So I sat and listened to her chat with the other fifteen or so writers in the room. I had expected a persona somewhat like that of her 2001 collection, Mercurochrome: raw, electric and inventive, by turns unruly and sorrowful. But her conversational voice was low and steady, her face open and calm. It wasn’t my first lesson in remembering not to equate the persona in the poems with the poet herself. But it was the first time that lesson made me sit up and listen. After Coleman died in November 2013, I went looking for her voice – that instrument that was both in her and her poems – to see if what I remembered about her voice, off the page, was as true as her poems. It was. I found it here, in her reading of “Requiem for a Nest.”

I met Wanda Coleman once, in the early 2000s. She came to Pittsburgh where I was a student, and in those years I didn’t know what to say to a writer whose work I admired (if I’m honest, ten years later, I have the same problem). So I sat and listened to her chat with the other fifteen or so writers in the room. I had expected a persona somewhat like that of her 2001 collection, Mercurochrome: raw, electric and inventive, by turns unruly and sorrowful. But her conversational voice was low and steady, her face open and calm. It wasn’t my first lesson in remembering not to equate the persona in the poems with the poet herself. But it was the first time that lesson made me sit up and listen. After Coleman died in November 2013, I went looking for her voice – that instrument that was both in her and her poems – to see if what I remembered about her voice, off the page, was as true as her poems. It was. I found it here, in her reading of “Requiem for a Nest.”

I never met Maxine Kumin. A dear professor introduced me to her work in the summer of 2000, with the book Our Ground Time Here Will Be Brief (1982). I then read everything Kumin had written, and I considered, for over a decade, writing her a letter of admiration, one that described our shared love of horses and nature, and the way her work gave me a permission to write about motherhood and the natural world like no one else’s. But out of procrastination, nervousness, and self-doubt, I never did. Then, on my thirty-sixth birthday in 2014, her obituary appeared in The New York Times. Someone else, finally, had written her the love letter she deserved.

If someone had told me, in the earliest days of the twenty-first century, that I would in the space of a year encounter two mentors in language and thought; that the mentors would be two women from opposite ends of racial, economic, and geographic experience; that those same women would over the course of more than ten years become two of the greatest influences on my own writing and thinking; and that these women would die within three months of each other, I would have disbelieved them. When I was in my early twenties and thought I knew what it meant to live an artistic life, I really knew nothing about anything. I wouldn’t say I know much more now. But back then, more importantly, I had no idea what it meant to have a mentor, much less see the end to a mentor’s long novel of art.

As I finish writing this, downstairs my daughter plays the piano, and the keys under her fingers sing her soul, a person whose face I know as well as my own. When I hear my daughter make music like this, it is like touching the pages of Kumin and Coleman, the words of writers who came before me, the poems that will stay past my life and into my daughter’s. Words crafted by women who never knew I loved them, but they shared their gifts anyway.

[i] “For All Your Flavorless Effort.” Mercurochrome, by Wanda Coleman. Black Sparrow Press: Santa Rosa, CA, 2001. 116-118.

[ii] “Catchment.” Selected Poems, 1960-1990. By Maxine Kumin. WW Norton: New York, 1997. 257-258.

Cate Hennessey’s work has appeared in The Gettysburg Review, Chester County Dwell, and Polish American Journal. Noted in Best American Essays, she has also been a finalist for the Annie Dillard Award in Creative Nonfiction.

When I finished reading Charles D’Ambrosio’s essay collection, Loitering, I wanted nothing more than to look away.

When I finished reading Charles D’Ambrosio’s essay collection, Loitering, I wanted nothing more than to look away.